Ozone-depleting chemicals detected by scientists in the atmosphere in 1951 – decades earlier than expected

An international team led by the University of Bremen, Germany, has uncovered evidence of ozone-depleting chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) in the atmosphere as early as 1951. This finding pushes back the known timeline of such harmful chemicals by two decades.

What are CFCs?

Chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) are artificially produced chemicals introduced in the 1930s, once widely used as operating fluids in refrigerators and air conditioners, and also as propellers in spray cans. CFC refrigerants, such as R-12 (dichlorodifluoromethane) and R-11 (trichlorofluoromethane), have been extensively utilized for decades in refrigeration technology applications worldwide, due to their good thermodynamic properties and chemical stability. However, in the 1970s it was discovered that these chemicals, when released in the atmosphere due to leakages in refrigeration units, system failures, and disposal emissions, as well as due to direct release when used in spray cans or as cleaning agents, caused the depletion the stratospheric ozone layer, which shields the Earth from harmful ultraviolet radiation. Because of this threat, many countries agreed on banning the production of CFCs under the Montreal Protocol, a landmark environmental agreement that has since helped the ozone layer begin a slow recovery (see our previous article).

An important discovery from historical data

Until now, 1971 was considered the date in which the first measurements of CFCs in the atmosphere occurred, thanks to the studies lead by the British scientist James Lovelock. Today, it has been discovered that these harmful chemicals were already present in the atmosphere much earlier than scientists previously believed. An international research team led by the Institute of Environmental Physics at the University of Bremen, Germany, jointly with scientists from the Department of Astrophysics at the University of Liege, Belgium, and from the School of Earth and Environment at the University of Leeds, UK, has detected CFCs in atmospheric measurements dating back to 1951, around 20 years before the experiments by Lovelock.

The breakthrough came from re-examining historical data collected at the Jungfraujoch research station in the Swiss Alps. In the early 1950s, scientists at the station used a spectrometer to study the sun, recording their measurements on long rolls of paper. While the original goal was to analyse the solar atmosphere, the measurements also contained information about gases in Earth’s atmosphere, a detail that was overlooked at the time.

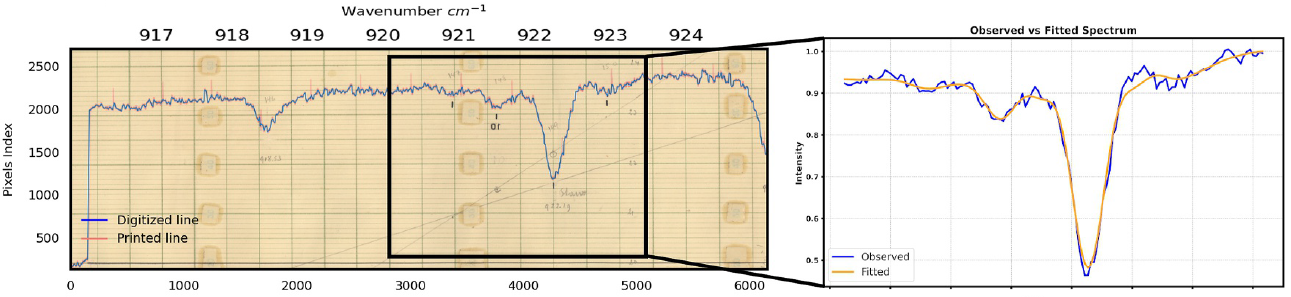

Using modern scanning and data analysis techniques, researchers digitalized these archived records and discovered clear traces of the CFC gas R-12 (alternatively known as “Freon-12”). This provides the first quantitative evidence of CFC concentrations in the atmosphere as early as 1951. In addition, the concentration measured by the researchers in 1951 was about 26 parts per trillion by volume (pptv), meaning 26 CFC molecules per trillion air molecules. This is nearly three times higher than what atmospheric models had predicted for that period, suggesting that early industrial emissions may have been underestimated.

The study, now published in Geophysical Research Letters [1], highlights the unexpected scientific value of historical data: by looking back in time, researchers can better trace the rise of air pollution and refine models that describe how harmful substances spread through the atmosphere. The same archival spectra might also reveal information about other atmospheric gases, opening the door to further discoveries about the Earth’s environmental past.

For more information, the scientific paper is available in open access in Geophysical Research Letters.

Source

[1] Makkor, J., Palm, M., Pardo Cantos, I., Buschmann, M., Mahieu, E., Wang, Z., Chipperfield, M.P., Notholt, J., 2026. First Measurements of CFC‐12 in 1951 at Jungfraujoch and Comparison to Current Measurements and Atmospheric Models. Geophysical Research Letters, Volume 53, Issue 3. https://doi.org/10.1029/2025gl117453